Automatic translation by Google Translate.We cannot guarantee that it is accurate.

Skoða vefinn á ÍslenskuThe Musical Chairs Framework for Understanding New Audiences and Innovative Practice: An Analysis from the Perspective of the Conductor

Majella Clarke

Introduction

New Audiences and Innovative Practice (NAIP) within the European Master of Music degree programme is offered by several higher music education institutions from countries in Europe including Iceland University of the Arts (IUA), Royal Conservatoire in The Hague, and Prince Claus Conservatoire in Groningen. The NAIP programme targets students with high-level performance skills interested in reaching new audiences by learning to develop and lead creative projects in diverse artistic, community and inter-cross-transdisciplinary settings. The programme is designed to develop students’ leadership skills and collaborative practice in a variety of artistic and social contexts. This article addresses the strategic positioning/s of an artist and its collective via the following questions: How can I position my artistic practice when considering traditional practice and familiar audiences, versus new ways of performing? And what might I need to consider if I choose to reorient, pivot or shift my practice?

This article will introduce the Musical Chairs Framework and present how it can be strategically used drawing on the author’s practice as a conductor and strategist. The article elaborates Chapter 2 from the author’s Master of Music thesis titled: Innovative Practice in Conducting: Graphic Scores, Sonic Batons and Open Ensembles for New Performance Formats.

Addressing new audiences and innovative practice from a conductor’s perspective is a complex task because as a traditional practice, it is taught through conservatory models of training that preserve the traditional practice. Typically, the conservatory models of education focus on classical music training, emphasising the repetition, reiteration, reinterpretation, and reproduction of repertoire from the late 17th – 20th centuries. However, in many education programmes, the role of the conductor as musical leader, artistic director, musician, composer, performer, within an historical context before the repertoire of the 17the Century is rarely discussed even though the practice has evolved and reshaped over several millenia and from when musicians started playing music together (Levine, 2001). When looking back through history, we can see that the ways of conducting and performing music does change over time, and will continue to change (Clarke, 2024; Clarke, 2025).

Technology developments of the twentieth century led to a redistribution of the almighty power of the orchestral conductor, and the democratization of orchestral life further led to the dilution of conductor power and the emergence of conductorless ensembles in the early 21st Century (Clarke, 2022). So, when it comes to understanding the potential for innovative practice within conducting, it needs to be placed within the full practice and historical context of conducting with all the traditions and their conservations. The symphonic traditions and associated conducting practices of the 17th – 20th Centuries continued to be enjoyed by audiences that are familiar with symphonic orchestra concerts, making that aspect of conducting practice still highly relevant to the profession. That being said, what happens when we take a forward looking approach to the practice of conducting? What types of innovations, expansions and augmentations of practice might we encounter in the 21st Century? And what might those novelties mean for orchestras, ensembles and their audiences? To be able to continue the analysis with depth, one must distinguish innovative versus traditional practices in conducting, as well as new audiences versus the familiar audience.

The Musical Chairs Framework

Drawing from almost two decades of experience in strategic management consulting, the Musical Chairs Framework has been developed by myself, the author, to understand the interplay and positioning between traditional and innovative practices, alongside new versus familiar audiences. Frameworks are commonly developed and used by management consultants to simplify complex problems, gain alternative perspectives, and create structure for developing analysis and understanding. They are also often used for gaining collective alignment on a current position for which a group main aim to shift from or pivot and can therefore be useful to guide a structured discussion. By developing a new framework approach, the complex problem of How can I position my artistic practice and what might I need to consider if I choose to reorient, pivot or shift? can be disaggregated and simplified. While the application in this article is with respect to my own practice in conducting, it can also be of use to other creative practices that might use the framework to position a pivot or shift in their own work.

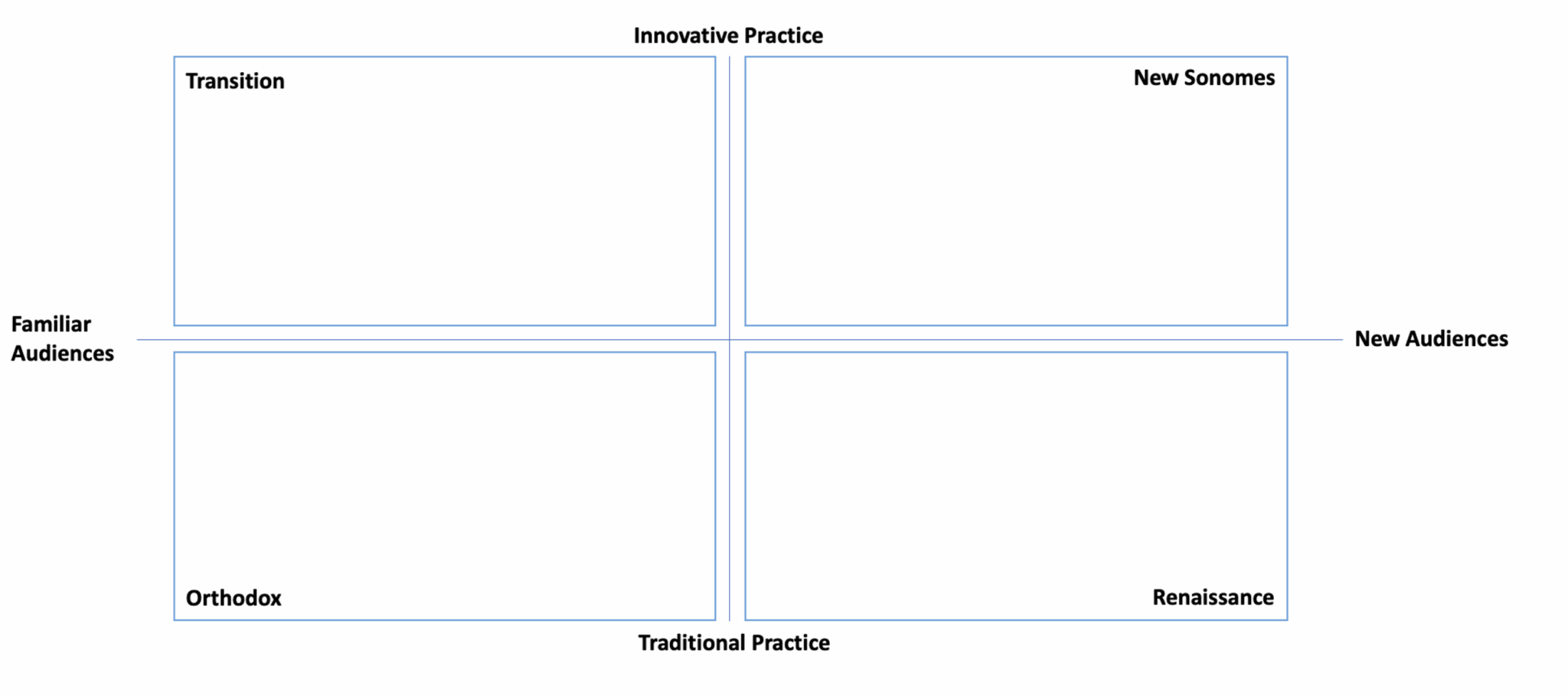

Referring to Figure 1 below, the horizontal axis presents the spectrum of audiences. Familiar audiences know the artistic format and often have familiarity with the repertoire and performance content. New audiences are those that have yet to experience the performance content and are usually looking for new creative experiences. The vertical axis reviews the spectrum of practice, from traditional to innovative. Traditional practice typically conforms to stylistic norms, notation, instrumentation, and performance techniques and can be argued to have deep cultural and historical significance. Innovative practice can incorporate the use of technology, the blending of genres, unconventional instrumentation, audience interaction, cross-media approaches, and cross-cultural influences to name a few.

Figure 1: Musical Chairs Framework

Quadrant Analysis

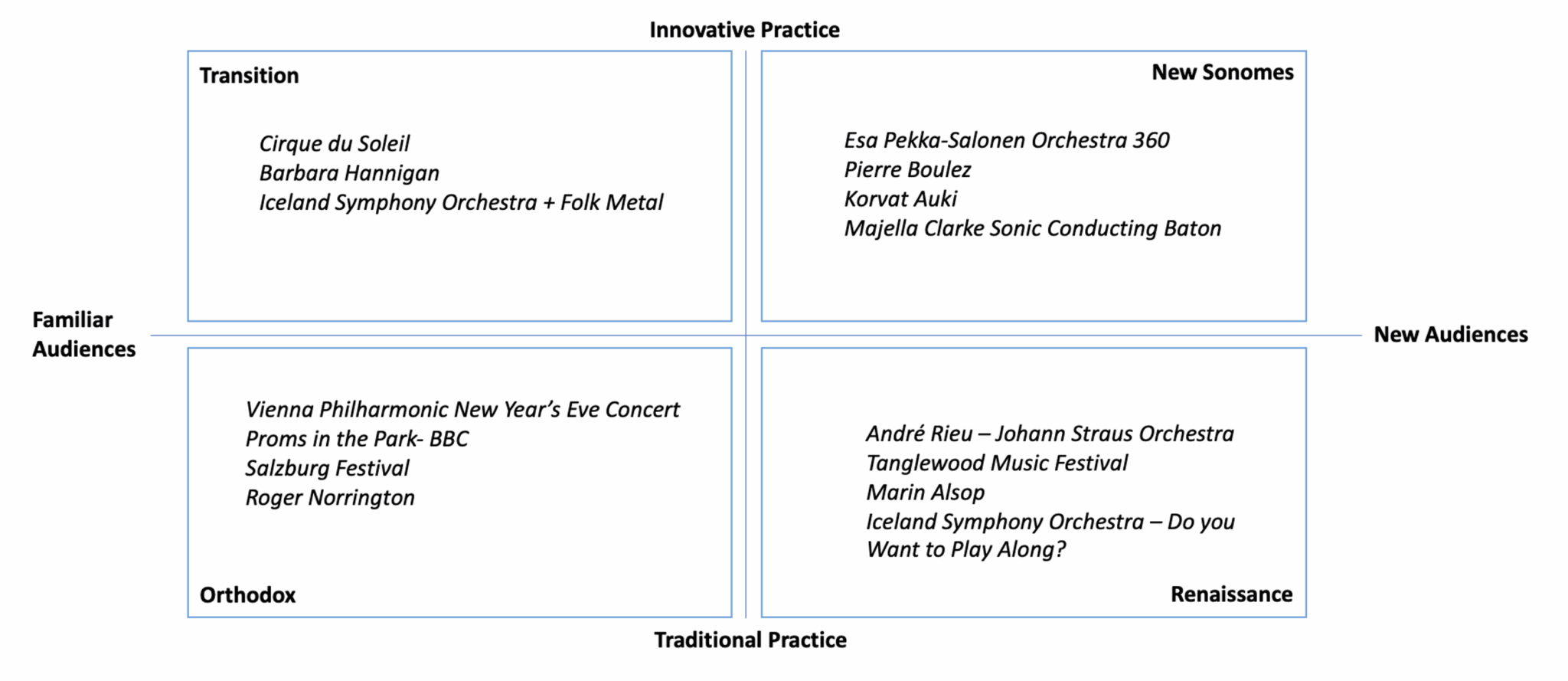

The following intersections can be used to describe the experiences when practice and audience converge in a section of the spectrum in Figure 2. Naming the quadrants and identifying key features of the quadrants helps us categorise and position the type of general experience that can be elaborated into one of four of the descriptions below.

Orthodox is typically used to describe something that adheres to traditional practices and standards or in accordance with established norms. It is the opposite of innovative. In the practice of conducting, we are looking for concerts that feature traditional (orthodox) programming and a familiar concert experience. For example, the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra at their New Year’s Eve Concert in the Großer Saal of the Musikverein in Vienna, commonly featuring a program of classical music compositions, particularly Waltzes and Polkas by Johann Strauss II. The Vienna Philharmonic’s web information about the New Year’s concert is a useful source to review the history and significance of what has become an orthodox practice in programming for the orchestra (Vienna Philharmonic, n.d.).

Transition is used to describe when the traditional audience begins to shift from a familiar to an unfamiliar experience and is likely to encompass various reactions and emotions that the audience goes through during the process. It can signify a change and adaptation that members of the audience go through as they shift from subscribing to traditional performance formats to innovative performance formats. Think Barbara Hannigan in concert. Hannigan is a conductor and singer who both conducts and sings at the same time, even though the concert experience is presented in a traditional staged format. Hannigan’s performance of “Mysteries of the Macabre“ composed by György Ligeti with the Avanti! Chamber Orchestra for the Festival „Présences 2011“ presents one of many available examples online (Bosc, 2011).

Renaissance is used to describe the experience of audiences with renewed interest in traditional concert formats. Usually this might be due to efforts to make the experience more accessible or relevant to contemporary audiences. The term expansion might be considered to convey the idea of broadening the reach of a traditional art form to attract new and diverse audiences. The conductor Marin Alsop has been an advocate for gender and diversity in classical music and has played a role in broadening the traditional classical music audience base. A review of Alsop’s projects presents extensive work towards diversity and inclusion including the Global Ode to Joy Project in partnership with Carnegie Hall, The Taki Alsop Conducting Fellowship to support women conductors, OrchKids for developing musical and social skills with schools in Baltimore, and Rusty Musicians for adult non-professional musicians in collaboration with the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra, (Alsop, 2023). Another example is the Iceland Symphony Orchestra, with its “Do You Want to Play Along?” project, inviting everyone who wishes to join the Iceland Symphony Orchestra into an open rehearsal and performance in the Eldborg hall of the Harpa Concert Hall to celebrate the orchestras 75th anniversary. Over a hundred musicians signed up to participate, along with the Iceland Symphony Orchestra.[1] The repertoire and presentation of the orchestra in its staged environment along with its conductor are traditional, with the program featuring the final movement of Dvořák’s 9th Symphony, From the New World, and Á Sprengisandi, arranged by Páll Pampichler Pálsson. However, the inclusion of more than one hundred additional musicians will most certainly invigorate the curiosity of new audiences, and therefore a good example of a project in the renissance quadrant.

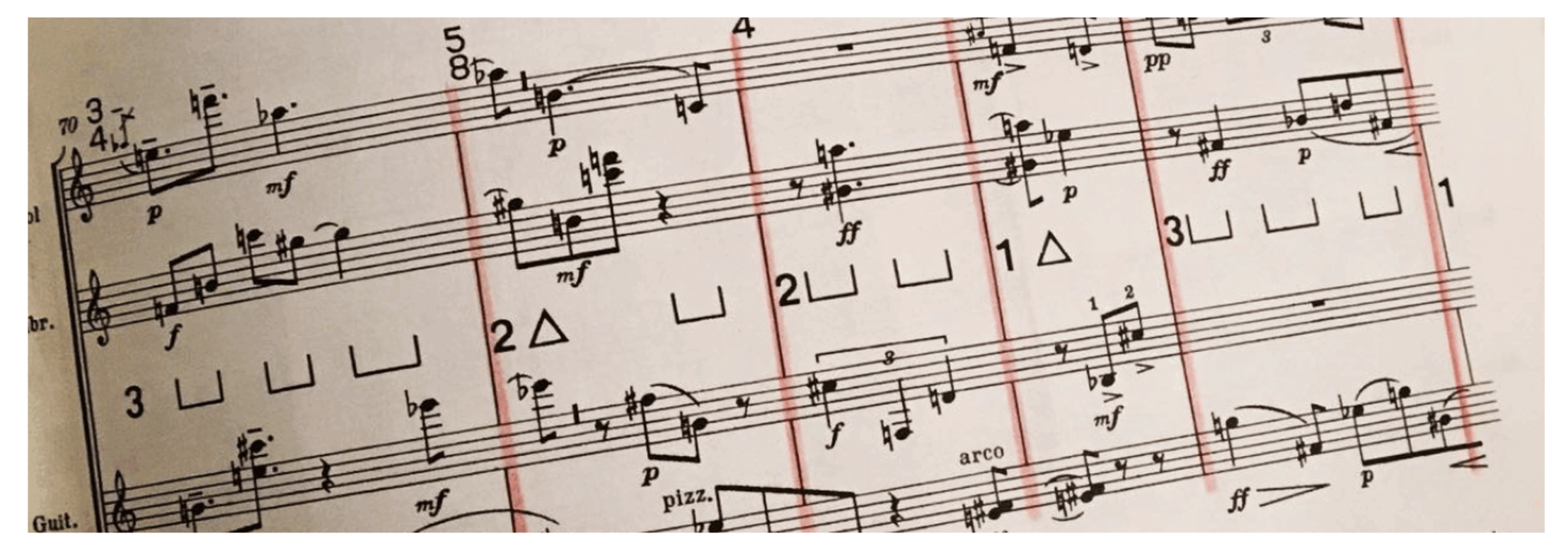

New Sonomes is used to describe the new audiences built around innovative practice. These include avant-garde, cross-genre, experimentalists and mavericks with eccentric, sometimes iconoclastic audiences. On the conductor front, Pierre Boulez developed innovative conducting techniques for conducting complex contemporary music, including a conductor notation; for an example, refer to Boulez’ score of Le Marteau sans maître (Boulez, 1957) in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Excerpt from the score of Le Marteau sans maître by P. Boulez

Esa Pekka-Salonen has explored innovative technologies such as orchestra 360 and conducting multimedia performances and has been at the forefront of innovation in classical music (HAM Helsinki, 2018). More recently, the sonic conducting baton developed in collaboration with Iceland’s Intelligent Instruments Lab, using neural audio synthesis (Caillon and Eslign, 2022) challenges the traditional foundations of conducting practice as it expands and sonifies the conductor’s gestures (Clarke, 2024). Using the conductor for directing spatially distributed musicians within the ensemble, so that the space itself becomes part of the ensemble, demonstrated in the world premieres performed by the Korvat auki ensemble at the Musica nova Helsinki Festival in 2025, is another example, Musica nova (2025).

Figure 2: The Musical Chairs Framework by Majella Clarke

Afterthoughts and Reflections

My NAIP project titled (Seasonally Adjusted) Sonomes performance, viva voce and thesis (Clarke, 2024) aimed to demonstrate innovative practice in conducting. It did this with the application of new technologies to sonify the conductor, while exploring different performance formats utilizing an open performative installation rather than a traditional staged concert experience to conduct graphic scores. New audiences were sought in the project by opening the experience to the public and by providing visual material and projections that can help the audience connect with the music and its performance. The word “sonome” itself is a confirmed neologism and it originates through the combination of the Latin word for sound (Sonus) with the Greek word Biomes, which primarily refers to biotic communities that exist in nature (Clements, 1917). The term biome was further developed to specify “a certain grouping of species and varieties is characteristic of each biome” (Shelford and Olsen, 1935) and the definition was further reviewed and disambiguated in the article The Biome (Carpenter, 1939), which reviewed all contributions towards the meaning of the word biome. The interesting word in the definition of biome was that of “community,” as the NAIP project explored different sound communities from both the performer and audience perspectives. In this context, the word Sonome is explored through identifying the intersection of new audiences and innovative practice spanning both conducting and new performance formats. The result is ultimately new communities of sound.

Positioning of Practice

Thinking about the type of audiences the expression of practice attracts is an essential consideration in performance. It determines the venue, the layout and spatial positioning of sensorial stimulus, the sonic, visual and gestual aesthetics and ultimately how to stage the performance. So, the performer needs to be aware as to whether they are intending to situate their performance in a traditional practice or an innovative practice. Reaching the right audience to present the practice is also an essnetial consideration. Familiar audiences continue to purchase tickets at staged performance venues and “bums on seats” is the performance metric that evaluates whether the performance achieved its goal. New audiences are likely to be different because it can be what data scientists like to call a “cold start” – that is, there is no previous reference to guide who you might reach out to, or who might be interested in your practice and artworks. This aspect of the new audience will require some experimentation in finding the vibe-tribe audience connections. My personal opinion is that the field of artistic research can support the experimentation and identification of new audiences that are interested in innovative practice, because the experimentation process that is inherent in artistic research allows for the exploration of new types of venues, sound making and how we make music. Therefore, when considering a reorientation, pivot or shift in practice, exploratories of time, space, sounding and ensemble, the different types of audiences one can reach also need to be considered.

Humanity Will Always Need New Ideas and New Ways of Expression

Innovation is a dynamic and often continuous process. However, there does come a point when an innovative approach expires or becomes mainstream or redundant. The music industry does protect innovative intellectual property, such as compositions, lyrics, sound designs and other contributions to culture with copyright laws. New instruments and musical technologies and software are often patented and licensed. These trademarks, copyrights, patents, and licenses have validity dates for which the right to use is transferred after a period (Givoni, 2015). While the duration of protection differs depending on the medium of expression, for sake of drawing a clear line, let’s assume that innovation loses its disruptive force when the intellectual property right protection lapses. In understanding that innovation is really a fleeting moment in the timeline of human creativity, it would point to the common phenomenon where all traditions that evolved over a short period of time were once innovations. This has implications for the application of the new audiences and innovative practice and the Musical Chairs Framework, as it means the categorizing of audiences and practice is dynamic, and that assignments of new audience and innovative practice are likely to become familiar audiences and traditional practice at a point in the not os distant future. The artist with their practice are challenged to create new ideas and find new people to receive these ideas. To remain in the traditional practice with the familiar audience risks cultural stagnation. Ultimately, the artist must renew themselves and ask – what am I giving that is new?

References

Alsop, Marin. 2023. “About Marin Alsop.” Marin Alsop, November 9, 2023. https://www.marinalsop.com/about/.

Bosc, René (@RebornBosc). 2011. ““Mysteries of the Macabre“ (G. Ligeti) par Barbara Hannigan.” Youtube. 23 April, 2011. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8ZKaMuALMMY

Boulez, Pierre.1957. “ Le Marteau sans maître.” London: Universal Edition.

Carpenter, J. Richard. 1939. „The biome.„ American Midland Naturalist 21, no. 1 (1939): 75-91.

Clarke, Majella. 2022. „Castles versus Cheerleaders: The Clash of Old and New Power Values and Their Effect on the Role of the Conductor.“ Leonardo 55, no. 5 (2022): 512-515.

Clarke, Majella. 2024. “Innovative Practice in Conducting: Graphic Scores, Sonic Batons and Open Ensembles for New Performance Formats.” Masters Thesis. Iceland University of the Arts.

Clarke, Majella. 2025. “The role of Technology in Expanding Conducting Practice and its Aesthetic Implications”. Presentation at the 50th International Conductors Guild Conference. Royal College of Music, London. 31 March 2025. https://www.majella-clarke.com/_files/ugd/729add_36f864355519480ab707b4890041aa87.pdf

Clements, F. E. 1917. „The development and structure of biotic communities.“ Journal of Ecology 5 (1917): 120-121.

Givoni, S. 2015. “Owning It: A Creative’s Guide to Copyright, Contracts and the Law.” Creative Minds Publishing. Australia. 2015.

HAM Helsinki. 2018. “The Virtual Orchestra: Esa-Pekka Salonen.” Youtube. 10 August, 2018. https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=gzOSdibHY0k

Levine, R. (2001). Dominant and tonic: Rethinking the role of the music director. HARMONY-DEERFIELD-, 15-25.

Musica nova. 2025. Convergent Pathways Performative Installation with Korvat Auki. 10 February 2025. https://musicanova.fi/en/event/korvat-auki-convergent-pathways/

Shelford, V. E., and Sigurd Olson. 1935. „Sere, climax and influent animals with special reference to the transcontinental coniferous forest of North America.“ Ecology 16, no. 3 (1935): 375-402.

Vienna Philharmonic. n.d. “Tradition and History.” Accessed December 26, 2023. https://www.wienerphilharmoniker.at/en/newyearsconcert/tradition-and-history

—

[1] https://en.sinfonia.is/concerts-tickets/open-session-with-iso